Minority Youth Bulges and the Future of Intrastate Conflict

Issue:Marginalisation

The global distribution of intrastate conflicts is not what it used to be. During the latter half of the 20th century, the states with the most youthful populations - a median age of 25.0 years or less - were consistently the most at risk of being engaged in a civil war or in an internal conflict, where either ethnic or religious factors, or both, came into play (an ethnoreligious conflict). However, the tight relationship between demography and intrastate conflict has loosened over the past decade. Ethnoreligious conflicts have gradually, though noticeably, increased among a group of states with a median age greater than 25.0 years, including Thailand, Turkey, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, and Russia. The salient feature of these intrastate conflicts has been an armed struggle featuring a minority group that is age-structurally more youthful than the majority populace. The difference in age-structural maturity reflects a gap in fertility between the minority and majority, either in the present or in the recent past.

Most social scientists are likely to explain a minority-majority gap in median age and fertility as the product of history and culture, an artifact of income differences, and/or the result of discriminatory policies or inadequate protections on the part of the state. While political demographers recognize these as contributing factors, they also argue that the political volatility and rapid population growth that are associated with youthful minorities are central features in a dynamic relationship known as the demographic security dilemma.

The demographic security dilemma, first described by Christian Leuprecht, arises when a state permits or promotes the political, economic, and social marginalization of an ethnoreligious minority. The more states marginalize a dissonant minority, turn a blind eye to a minority's exclusion from mainstream social and economic participation, or allow minorities to exclude themselves, the wider the majority-minority fertility gap and the more rapidly those youthful minorities grow as a proportion of the state's population. Minority youth bulges naturally lead to political tensions. Notably, minority-state tensions do not naturally emerge out of the opposite circumstance: when the majority is youthful and the ethnoreligious minority is not.

What can governments do to prevent the minority-majority fertility gap? Make sure that health, family planning, and educational programs are extended equitably to minorities. An absence of proactive policies to bring youthful communities into the economic, social, and political mainstream tends to strengthen radical and traditionalist religious political organizations, which often take advantage by filling in gaps in local services and governance. Typically, they restrict girls' access to education, thwart women's attempts to gain social and economic autonomy, restrict speech, and campaign against modernization and secularization.

How can foreign affairs analysts forecast risks associated with youthful minorities? That's easier said than done. Due to restrictions associated with ethnic and religious data collection and the political sensitivities surrounding conclusions drawn from these data, relatively few countries currently provide public access to data that are disaggregated by ethnic and religious affiliation. For now, analysts attempting to estimate qualities of a minority's age structure must approximate from related measures, such as estimates of minority birth and death rates, fertility rates, and school attendance. Rather than being accessible from a central source, these are published in scattered government reports and in the international demographic and public health literature.

Despite ongoing high fertility across sub-Saharan Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, UN demographers foresee a world in the not-too-distant future that will be dominated by states with populations near or below replacement-level fertility (just above two children per woman). In that future, analysts can expect the ethnoreligious composition of many states to be extremely sensitive to minority-majority fertility gaps.

However, understanding the implications of minority demographic trends could hinge on the ability of researchers to gain access to sub-national ethnoreligious data. For this to happen, some governments will have to overturn laws that currently prohibit identification by ethnicity or religion, while data collectors will need to promote conditions that encourage survey participants to self-identify their ethnic and religious affiliations anonymously, and without fear.

Article Source: The Stimson Center

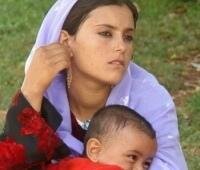

Image Source: CharlesFred

Delicious

Delicious Digg

Digg StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Reddit

Reddit

Posted on 14/11/11

Comments

Post new comment